Governance & Risk Management

,

Patch Management

Google Report Lauds Transparency and Researchers, Warns Against Incomplete Fixes

•

July 31, 2023

Why are so many fresh zero-day vulnerabilities getting exploited in the wild?

See Also: Evaluating and Reducing Supply Chain Risk

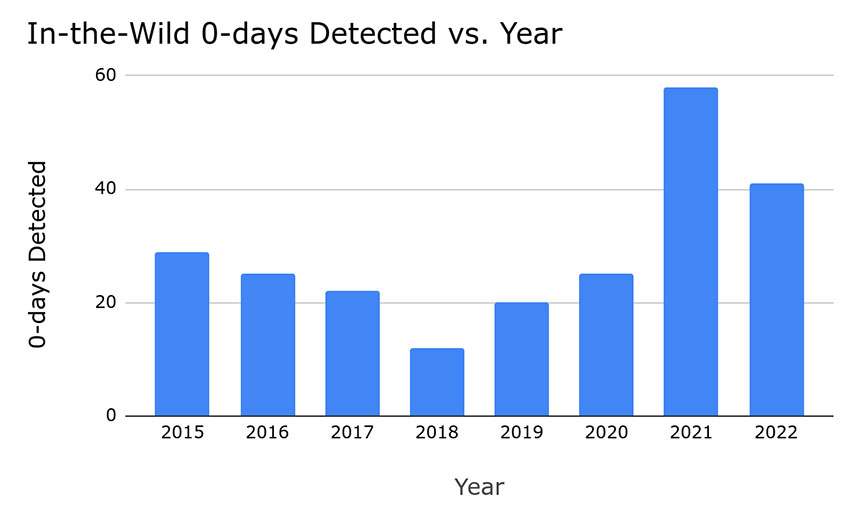

A new study from Google says that last year, 41 new zero-day vulnerabilities were exploited in the wild. While that’s welcome news in terms of recent volume – it’s a 40% decrease from the all-time annual high of 69 in 2021 – it’s still well above the annual average compared to 2015 onward.

Zero-day vulnerabilities are dangerous because they allow attackers – who are oftentimes spies but sometimes criminals – to amass victims, frequently without the victims becoming aware until it’s too late. But simply counting the number of zero-day flaws that are found every year isn’t a guide to whether things are getting better or worse, and also cannot account for how many zero-day exploits are being used in the wild but haven’t yet been detected by the “good guys.”

One reason so many zero-day flaws were discovered last year – over the average since 2015 – is likely thanks in part to vendors being more transparent, said Maddie Stone, a security researcher with Google’s Threat Analysis Group, in a blog post.

Unfortunately, 40% of the new zero-days discovered were variations on zero-day vulnerabilities vendors had already patched. Sometimes, vendor fixes were part of the problem because they added new, exploitable flaws to the code base.

“The continued work on detection and transparency from vendors is a clear win, but the high percentage of variants that were able to be used in-the-wild as 0-days is not great,” said Stone.

Another welcome change is that attackers wielding zero-day exploits have been targeting browsers less than before. Zero-day exploits found in the wild targeting browsers have dropped by 42% from 26 in 2021 to 15 in 2022, Google reported.

This change is likely due in no small part to better browser defenses forcing attackers to look elsewhere, said Stone. This of course is good, and she lauded browser manufacturers for not just patching zero-days in their products, but for also looking much more deeply at root causes and locking down the attack surface to prevent whole classes of flaws from being exploited.

One consequence of browsers becoming harder to hack is a shift in attack strategies. Google reported that in 2019 and 2020, hackers used zero-day exploits in watering hole attacks, which involve a victim being lured to a website where their browser could be hit with the exploit, which would then infect the system with malware. In 2021, attackers shifted to one-click attacks for zero-day flaws, which attempt to trick a target into clicking on a link that leads to a site set to exploit their browser, it says. In 2022, many attackers shifted to zero-click attacks that require no user interaction. These attacks can be extremely difficult to detect. Some zero-days are arguably worse than others.

Android’s Patch Gap

Some zero-days also have a worse impact than others, depending in part on the ecosystem in which they exist. Users of the Google-developed Android mobile operating system, for example, are faced not just with the threat of vulnerabilities being exploited in the wild that the good guys don’t yet know about – zero-day exploits – but also n-days. The “n” stands for “known,” referring to flaws that were previously a zero-day but for which a patch has now been issued.

The challenge for Android users is access to patches. Just because the Open Source Project team that develops the Android code base issues updated code or security fixes, there’s no guarantee when, or even if, those fixes will make it downstream and onto any given device. Another challenge is that it might take a substantial amount of time for a vulnerability in one part of the ecosystem, such as a processor used by only one vendor, to get fixed and for the fix to be added to the Android code base. During any of these types of scenarios, too many n-days are functionally continuing to work as zero-days for attackers, Google warned.

“While these gaps exist in most upstream/downstream relationships, they are more prevalent and longer in Android,” Stone said.

Many Android device manufacturers customize the operating system before pushing it to their devices and due to their development pipelines, they might not get even critical security fixes into the wild for months. Also, while no device manufacturer commits to releasing updates or patches in perpetuity, some Android device makers may only do so for a relatively short period of two years after a device has been introduced to the market. Of course, most users will continue to use the device for much longer.

Bug Collisions

When more than one researchers discovers the same vulnerability, there’s a bug collision. Google said that while the frequency of this occurring is tough to measure, it seems to be happening more often, based on how many zero-day exploit security alerts from vendors credit multiple researchers with having discovered the underlying vulnerability.

Stone said vulnerability researchers’ expertise in increasingly complex code bases and their propensity to publish research reports are also likely reducing attackers’ ability to benefit from any zero-day exploits they might wield. In addition, a greater number of zero-day vulnerabilities spotted by researchers in 2022, compared to previous years, have already been getting exploited by attackers.

As a result, “when an in-the-wild 0-day targeting a popular consumer platform is found and fixed, it’s increasingly likely to be breaking another attacker’s exploit as well,” Stone said. “We hope that vendors continue supporting researchers and investing in their bug bounty programs because it is helping fix the same vulnerabilities likely being used against users.”